Oh good, more prose poetry-based obscurantism from some Frenchman with a good PR department and a fan club. My translation is by Sheila Faria Glaser.

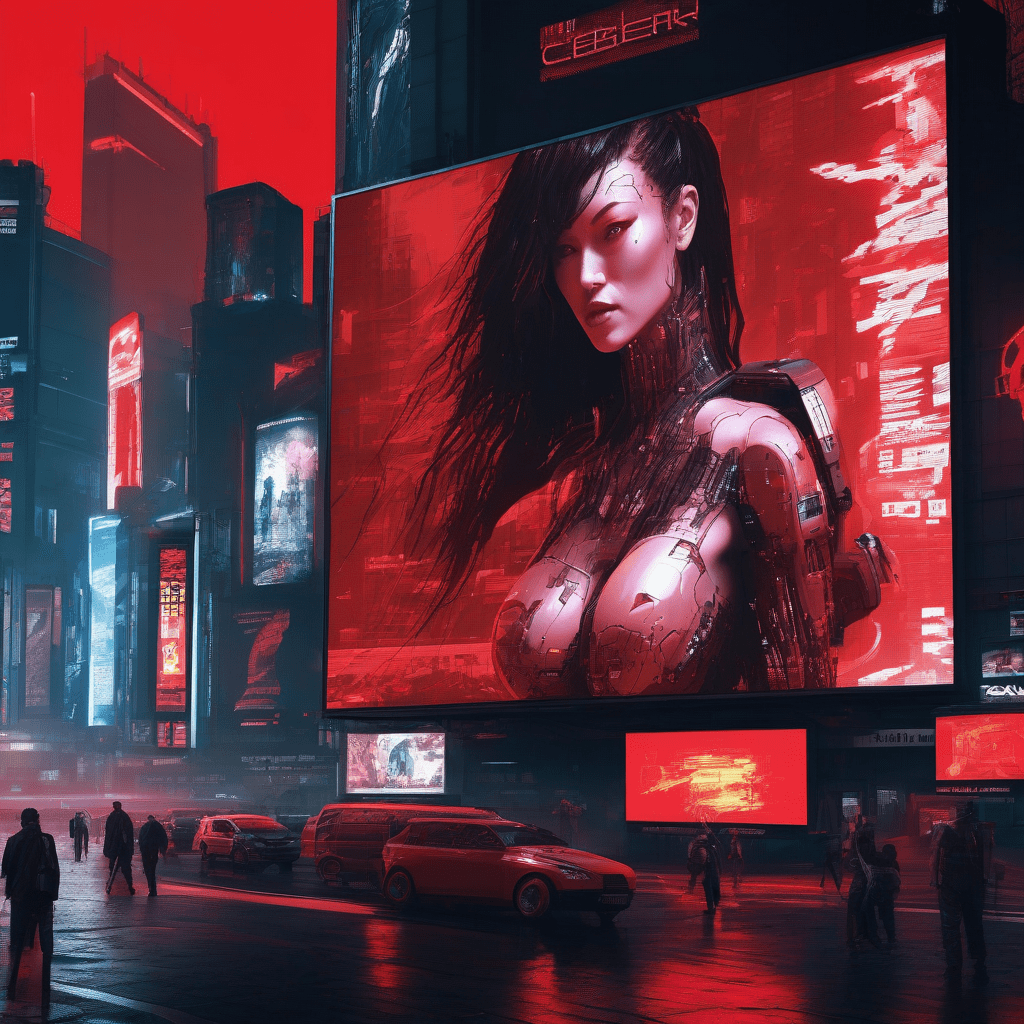

I’m fascinated by the commodification and weaponisation of images and symbols, and the vague nebula of rules and interactions that make up this element of the human social framework. So this was an obvious go-to.

Simulacra and Simulation was originally published in 1981, Baudrillard died in 2007, meaning he had time to witness the anarchy of the growing internet and accompanying cyberculture. In many ways, as many have pointed out, Simulacra and Simulation remains incredibly relevant to the modern world, in ways that Baudrillard could never have predicted. In some ways, becoming more so as we stagger further into the 21st century. Unfortunately, it is also firmly mired in the perpetually eye roll-inducing morass of French obscurantist psychobabble so characteristic of its context. Meaning that, while the book starts out with some interesting content, as you progress through it, there’s an increasing amount of verbiage, and a corresponding decrease in the amount of meaning.

I’m frustrated by Baudrillard, because I get, broadly, what he’s getting at – and genuinely agree. I just wish he’d have said it in a less ridiculous way. Take the replication of Patrick Bateman analogues through 21st century society, driven by the ascendance of signification over utility. This is exacerbated by the modern world, but if you take authors like Bernays’ Propaganda, Will Storr’s work in The Status Game, or extrapolate down from something like Hadnagy’s Social Engineering or de Mesquita’s The Dictator’s Handbook, then you start to see that the human tendency to trade in symbols and signification is not, in any way a modern thing. Advertising, and the media at large, just understood the mechanics and capitalised on that tendency. This is more a case of ‘don’t hate the player, hate the game’. If humans are too ill-equipped to figure out how to prioritise value assignments, then that’s a problem with humans, not the fact that symbols have an exchange and a utility value in the framework of human thought.

At times, this book seems like fifty pages of meaningful content stretched over thrice as many.

Maybe it’s the Englishman in me, but after a belly full of ‘continental’ philosophy – and the probability of more down the line – I don’t know why I’m surprised that the majority of French philosophers I read seems to have so little argument, explanation, or substance of any kind. Yet most seem to be bloated with hot air in the form of allusions, in-group references that don’t amount to much and scientific inaccuracies. It’s like being in a bad clique of an American high school but with superior linguistic capabilities and featuring guys who are mostly dead.

‘Continental’ philosophy seems to have more to do with aesthetics than argument and honestly I really wonder how anybody took them seriously. What weird spasm of inbred cultural inanity led to a demand for this lot scrawling great reels of text, the vast majority of which seems devoted to pointless posturing and obscurantism?

I can already hear the tedious parade advancing with predictable timing and pseudosuperiority: “Ueeruruhghgh you justttst dunntt gettiiiiiittttt”

That’s the point, you pseudointellectual hacks. This isn’t a matter of intelligence. This is a matter of communication. It seems like the majority of the contemporary French ‘continental’ guys fail. Utterly. Consistently. And maybe some idiots think quoting jargon at each other makes them part of some mensa-level group for special people. I get it, the lockdown twitter trend of quoting Deleuze and Land was funny. For my money, however, those texts have more value as aesthetic experiments than they do as functional or effective methods of idea communication. The rest of it is just a social status game. If it helps you to believe that being in the in-crowd gives you some greater social value, then, by all means – keep right on. The rest of us have jobs.

Part of my industry is ensuring that PHD-level academic biomedical copy, often from people who don’t have English as a first language, is intelligible to an English-speaking audience. People are paid to interpret the semi-coherent sentences of incredibly specialised PHDs from around the world, and translate them into coherent English and make sure they say what the author actually wants them to say.

Deleuze, Derrida, Hegel, Lacan, Baudrillard, et al. – all write well-crafted sentences from a purely grammatical point of view. Which means that they very much understand how to use their respective languages – translated or not, it’s irrelevant. Because only about one in every fifteen of those sentences will contain some sort of information. Of any kind.

So my question is: Why is it that a bunch of highly educated people, ostensibly attempting to fashion coherent arguments about all sorts of interesting topics, communicate a thousand times worse than people who can barely speak English.

“Oh, because the topics are very complex.”

Sew your mouth shut with rusty cheese wire. Biomedical science is also reasonably complex. I don’t know if you got that memo. The base level of communicative aptitude presented by authors from, for example, China, writing in a secondary or tertiary language, is often far superior and more coherent, than the best output from these French “intellectuals”.

“Oh, well, you just need to start at the Greeks.”

Been there, done that. Plato/Socrates, at least had arguments that, while long winded and taking various ideas for granted (owing to the limitations of technology and writing and recording etc at the time – so pretty forgivable) had coherent arguments. Much of, say, The Republic, seems kind of shaky. Socrates’ argument with Thrasymachus is especially questionable from the point of view of its framing.

Then you’ve got – in no particular order – Descartes, Hobbes, Kant, Hume, Mill, Machiavelli, Bentham and a hundred other guys – all making arguments. Often incredibly dense multi-layered difficult arguments that require a couple of re-reads to get. But they’re identifiable as arguments. And they follow those arguments up with justifications. Using logic and reasoning. And they point to examples or they give thought experiments to illustrate an idea.

So what the fuck happened to these idiots in 20th-century France? Because all of the foundational basic elements of a coherent rational intelligible argument are missing.

“These are difficult texts.”

I’m not sure that’s true. The core ideas in Simulacra and Simulation are interesting, but I don’t think they’re remotely as complex as people like to make them out to be.

At least Heidegger had the excuse that – as far as I understand – the word ‘dasein’ is used in multiple different ways depending on context, so the experience of Being and Time is a nightmare of reading/hearing the world ‘dasein’ five times a sentence and then wondering if you’re having a stroke.

You don’t have that excuse here. The early few chapters are interesting but the meat seems increasingly sparse the further you progress, and no amount of ‘drilling down’ into said ideas seems to track with because the sentences you’re reading are only vaguely connected and are not really referencing or expanding on the ideas that preceded them. Mostly it descends into semi-coherent babble.

This is why you have the “Parisian nonsense machine”. I’m inclined to agree with Sokal and Bricmont when they describe this trend of idiocy as ‘intellectual terrorism’. Half of these morons keep throwing in pseudoscientific terminology. The problem being that the scientists who actually understand these fields cannot for the life of them understand what the fuck authors like Baudrillard were trying to say, and thus we can only conclude that the chronic use of, sometimes entirely fictional, jargon like “multiple refractions of hyperspace” hon hon hon, is just there to give them a veneer of intelligence to idiots who think that’s the kind of thing smart people say.

If Simulacra and Simulation (and seemingly a great deal of French 20th century philosophy) often seems to be utterly unintelligible, there’s a chance that it’s because Baudrillard might not have that much of substantive value to say on his own topics.

Take, for instance, this quote from page 84, ‘The Implosion of Meaning in the Media’:

“This absence of a response can no longer be understood at all as a strategy of power, but as a counter strategy of the masses themselves when they encounter power. What then?”

Well, does he have any examples to back that up? Because that’s an interesting assertion, and I’d genuinely like to hear more about it. But here’s how arguments work: If you can’t show your working outside of just jabbing a finger pointing at films and name dropping other texts and authors, then this is yet another episode of valueless masturbatory word salad, from a group of people who seem to produced nothing but masturbatory word salad.

As Sokal and Bricmont illustrated in Fashionable Nonsense, Baudrillard has a bad habit of randomly co-opting mathematical scientific terminology that he has no business using and clearly doesn’t comprehend, and not only misusing it, but misusing it while saying absolutely nothing – even in a metaphorical sense. That’s actually quite an impressive feat.

The fact of the matter is that sooner or later you have to ground your ideas in the real world for anybody to take them seriously. I know, I know, nothing is really real because hyper-reality blah blah blah, therefore you can point to The Emperor’s New Groove and we should all agree that it’s actually a documentary.

But that’s not how any of this works.

Either provide an argument and evidence, or fuck off.

I’m left with the impression that this is one of those books you can reference sparsely when you want to argue something on ‘hyper-reality’ and how signs and so on now play an outsized role in our lives, whether we realise it or not, whether we partake or not – off hand, I’m thinking of flex culture, Veblen goods, influencers, etc – but the bits from which you can take substance are surprisingly sparse.

Returning to ‘The implosion of meaning in the media’, one hypothesis proposes that information produces meaning without signification. ‘Message’ and ‘content’ are separate from meaning. Meaning is lost faster than it can be ‘injected’ – so a net decrease of meaning over time.

“One must appeal to a base productivity to replace failing media” – this is not remotely clear. How is he defining base? Is he talking about sheer content output volume? Because that has been a major driving force of the content marketing industry for the last 20 years. So much so that the humans involved in that side of the industry are effectively replaced by contemporary large language models – ie: ChatGPT – because the quality of the output is completely superseded by the volume of output. Do you want a 500-word blog post on composting? You could put a job up on a content mill like Copify, or you could save time and get the content out of ChatGPT. Anyway…

The broad adoption of information spam constitutes the ideology of free speech, apparently. A multiplication of independent information sources, such as pirate radio, constitute ‘antimedia’.

Is Baudrillard against independent media, here? How is independent media ‘antimedia’? Does that imply that only established outlets of significant enough scale constitute media? How in the world do you make that leap?

“Or information has has nothing to do with signification.” Baudrillard seems to position information as its own entity, detached from any baseline – it seems to represent some kind of unknown, ‘an operational model of another order’, ‘outside meaning’.

It’s unclear how Baudrillard is even defining information here, but at times I wonder if he was putting the cart before the horse. Information can’t be divorced from meaning, as meaning is derived from information. You can’t create meaning without taking it from some form of information. Unless Baudrillard has decided that we should be interpreting the notion of ‘information’ in some new way, it’s hard to agree with him on the detail of his arguments. The broad swathes are interesting, but it’s debatable whether he’s actually trying to create a coherent argument for them, or is just padding out an extended shower thought. At times he seems to be trying to dissociate information and meaning, but because the one – meaning – is derived from the other – information – I’m really not sure how one can decide that they aren’t.

He continues into a bit on ‘Shannon’s hypothesis’ and flags up genetic code, monads and then ‘chance and necessity’. And this is just reads like him playing some kind of word association game with himself. None of it links to anything else, it’s just a dribble of nouns that are framed as if they’re a single coherent thought, but don’t actually relate to each other.

The loss of meaning is directly linked to the dissolving action of information and mass media. How? Is this an assertion that information itself causes the loss of meaning when provided by mass media outlets? This is at right angles to the previous point about media only being media when provided, presumably, by a large organisation. More to the point, this just seems fundamentally weird and illogical. If mass media creates an absence of meaning then the agent of that absence of meaning is more attributable to the amount, rather than the information itself. If Baudrillard is complaining about the fact that the flood of information creates a parallel flood of interpretations and meanings, leading to some people having a hard time discerning what is ‘true’, then his beef isn’t with information, it’s with the volume.

I think I get his bigger ideas, but they fall apart in the details. Another one of those instances where something looks like it’s sturdy until you squint at it, and then you realise it’s being held together with papier mache and hope. I don’t really agree with a lot of what seem to be passing for substance in his arguments, and elsewhere the points he’s making just seem to be reinterpretations of fairly basic concepts that he then uses to somehow arrive at completely baffling conclusions. I can only presume that the definitions he’s using for his arguments are very idiosyncratic, because when you apply standard definitions to the pieces of these ideas, and how they relate to one another, what he seems to suggest doesn’t track, and doesn’t even seem to support at his overarching points. Other times entire chapters, like ‘Holograms’, just seem to be incoherent streams of arbitrary babble, devoid of meaning or content. He’ll invoke the central noun, but how it relates to anything is anybody’s guess.

Again, I can only conclude that Baudrillard is mostly just full of shit. he makes a lot of bold statements and then arrogantly expects people to just accept them and take him at his word. Not how that works. Sorry, mate.

I’m fully willing to accept the idea that I’m misinterpreting a lot of this stuff and missing the point in others, etc, but I don’t think that’s my fault. If you’re going to write like an idiot, then you forfeit the right to be snooty when people completely miss whatever point it is that you are trying to make. Yes, I’m sure there’s a small circle of sad losers who use obscurantist bollocks as a masturbatory aid for some weird fantasy that they belong to some kind of elite circle, and I guess if it gets them off, then whatever. I’m not buying it. Was this guy ever introduced to an editor? If this came past my desk, I’d throw it in the bin.

I’d like to think a second or third reading, etc, would disabuse me of such a notion, and perhaps reading with a more focussed lens or intent would provide enough of a structure to hang some of the more nebulous material on. On the other hand, I think it’s to the book’s detriment that I have the impression that I need a secondary framework on which to drape all of these chapters in order to make them seem less two-dimensional.

Somehow, the weird artifice of this book may actually be the best illustration of its central idea. It’s sort of a weird representation of itself, projecting an image of grand theorising that only works if you accept the image of it containing grand theorising. But it’s ultimately hollow.

Leave a comment