Deliberations on dehumanisation.

I came to this one largely because I’d started to come up with some ideas about dehumanisation, but much like Livingstone Smith addresses in the opening chapters of his book, Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization, when I tried to answer the seemingly basic question, ‘what is dehumanisation?’, I found a simple satisfactory definition eluded me. I had some kind of vague boilerplate for the general concept, the same one I imagine most of us have to a greater or lesser extent.

The specifics of that boilerplate are harder to get at. You ever squint at an idea that seems clear but gets foggier the closer you look? Try running it through some cursory Socratic-style questioning and you might see what I mean. I turned the concept around a couple of times and came to the conclusion that I didn’t know enough about what I thought I knew. So a bit of searching later, I came up with this book.

I was a tad relieved to find out that someone else was having as difficult a time nailing the concept of dehumanisation down. I was half barking up the wrong tree with this one, to be honest. I had some kind of malformed thesis, but it was more aligned with ‘mechanistic’ dehumanisation’, a concept advanced by Nick Haslam in his 2006 paper, Dehumanization: An Integrative Review. That paper, however, is not important to Livingstone Smith, who references the idea once in a paragraph and discards it. So for my own personal hobby horse, I’ll need to look elsewhere. Nonetheless, this book is a valuable starting point for idiots like myself.

As you might expect, a great deal of the material here revolves around American slavery and the Jews in relation to Nazi Germany. There is a good amount of other historical material, but for obvious reasons a large amount of our case studies, for lack of a better term, regarding dehumanisation comes from these two examples. Fair warning: even for the calloused 21st century soul, some of this stuff is difficult to swallow. If you’re going in cold, some of the specifics might be a bit of a slap in the face. It’s easier to stomach if you’re at all familiar with some of this history or adjacent subjects already. This topic, and everything associated with it, is ugly.

Books that I drew parallels with while I was reading this included Miri Rubin’s Cities of Strangers, chiefly for its outline of the social position of Jewish people during the medieval period, and the introductory chapters of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. You don’t need any of this, but it might be useful or interesting.

There is a fascinating record of Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, he of the single bollock, and patron of the Gestapo Dance, visiting a pre-concentration camp execution ground to witness the mass executions for himself. He was there to bolster the Einsatzgruppen troops following reports of morale issues. It turns out that asking men to mechanically gun down rank on rank on rank of Jews, Serbs, et al., takes a toll. Eventually some of them simply refused to kill anyone else, prompting Himmler’s visit to Minsk. The records detail the execution squads being so psychologically devastated that even with the victims lying face down on the ground with the guns to the back of their heads, the executioner’s hands shook so much that they continued to miss, injuring them instead.

Himmler himself was unable to deal with what he was witnessing. Reports note him being pale, unable to stand still, displaying high levels of anxiety, and looking at the ground following every volley of gunfire. He is supposed to have panicked and screamed at the aforementioned executioners when they were unable to perform their tasks.

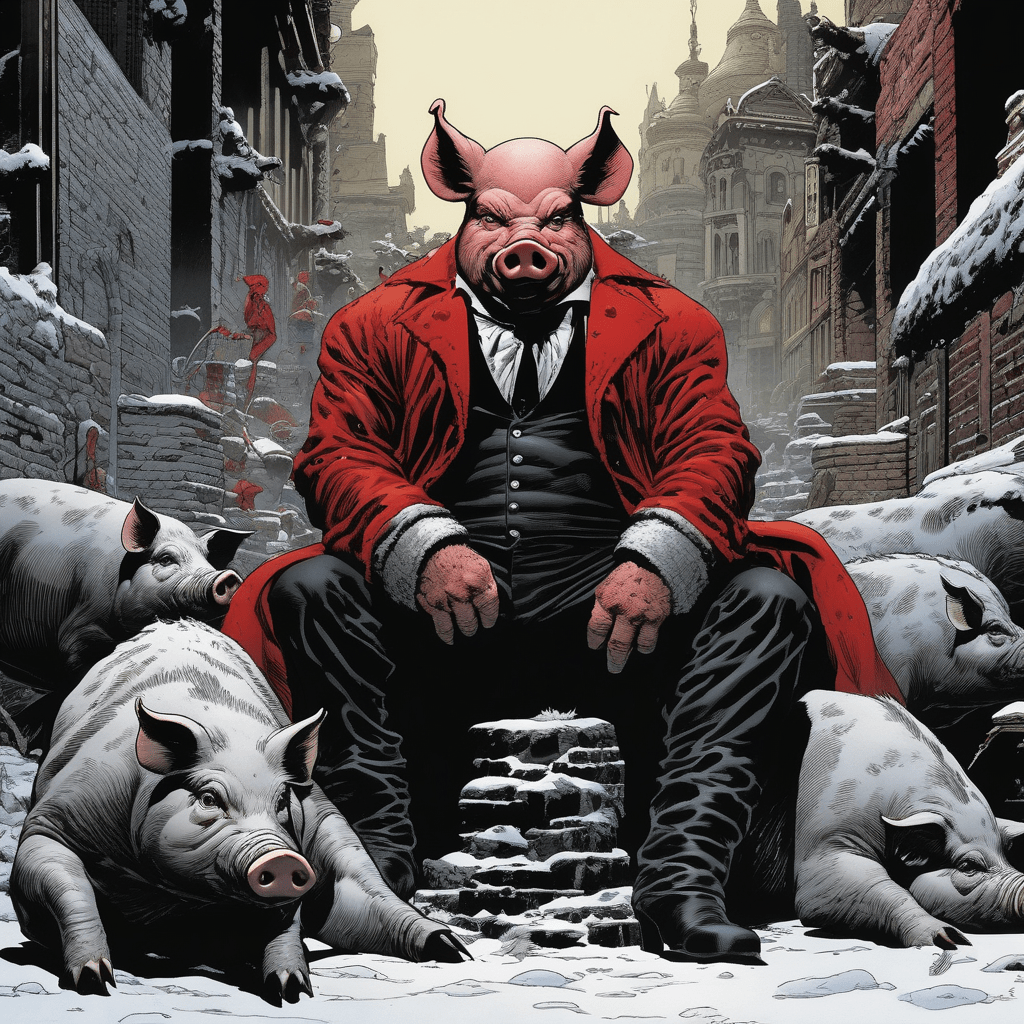

Without intending to undermine the severity of the holocaust, am I accurate when I say that we tend to think of people like Himmler as being almost comic-book-villain-esque? Absurdly proud of their actions and prone to revelling in the carnage they orchestrate. But sections like this serve to illustrate how even these supposed figureheads were unable to look their own mechanical horror in its bleak unflinching eyes. The back third or so of the book expands on a theory as to why this might be – how even in the midst of dehumanisation, our own minds tend to betray us. We cannot quite fully abandon our recognition of other members of the human race as being such, however much we might despise them or however far below us we might consider them on ‘the great chain of being’.

I’m presented with a problem – an ironic one at that – how do I choose to interpret this report? It in some ways humanises a man I would otherwise consider a monster – someone you’d put a knife in for the greater good. But if he were a monster in the archetypal sense, would he react in such a fashion, even to people he refused to recognise as people consciously? This doesn’t excuse anything, not by any length you could concieved of, but maybe it alters the way you percieve events. And maybe you would slit his throat for the greater good, but maybe there is also a psychological difference between killing a monster and killing a man. It would, if the Einsatzgruppen are anything to go by, seem to be the case.

The conclusion one draws from such a record is that one does not need to be a monster to commit atrocities. We are conscious of that fact at an intellectual level, but I’d put money on most of us being unwilling to consciously accept it on an emotional one. Because accepting that idea in turn draws us all onto the same level. We’d characterise Himmler and the Nazis as monsters because we dislike the notion that they were in any way shape or form, like us – Nuremberg defence be damned. We don’t think of ourselves as being capable of partaking in a racist genocide. And so Himmler must be a monster, and a monster revels in the carnage and the suffering that they create. But the evidence is against us. He could not stand his own carnage – no doubt that fact distressed him as much as the executions – and neither could his subordinates. And thus we have an explanation for the gas chambers. A grim one, but an explanation nonetheless. It’s not a comfortable thought.

I’m not sure that I’m entirely on board with Smith’s definition of dehumanisation – perhaps I was hoping for something not quite as long but conveniently wrapped all the issues up in neat little box with a bow? I do wonder whether it dwells too much in pre-contemporary times. Despite its publication in 2021, there is little material that draws on events after roughly the 1950s. This is my own biases and hobbyhorses creeping in, I concede, but I think the march of technological progress – as necessary and inevitable as it is – reveals increasing conflicts with biology; and this particular aspect of dehumanisation will be increasingly relevant as we continue into the 21st century.

Under Smith’s terms, I imagine you could make a reasonable argument to dismiss the idea of industrial and economic dehumanisation, but one has only to look at reports of factories from the industrial revolution to see the overlap – and if some of that strain of horror doesn’t fall under ‘dehumanisation’, I’m not sure in which category we should file it. How do you square biocentric dehumanisation theory with the commodification and disposability of humanity? I wonder if viewing dehumanisation on mostly, if not exclusively, biological terms ignores the reality of the modern conception of a human within a technocapitalist framework. Or, for the sake of balance, the rendering down of humanity to mere chalk marks under the various communist regimes of history? These are not – as any instance of slavery demonstrates – modern phenomena. It’s all economics. The march of progress might have revealed, as a systemic by-product of supply and demand, what effectively seems to necessitate the rendering down of all organic matter into economic units and measurements of output.

Perhaps these concepts are explored in other works by Livingstone Smith, or perhaps the overlap between economics and dehumanisation is an area he’d prefer to leave to others, which is entirely fair, but I think it is worth considering.

Whatever the case, I am entirely incapable of offering an adequate rebuke or alternative, much less an improvement. I certainly wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it to anybody wanting to gain more than a pop-culture understanding of the subject at a broad level. The former chapters may be more interesting to the historically oriented, while the latter may be more interesting to media-oriented individuals. To my unacademic and ill-researched mind, it is comprehensive and well researched, and at some point in the future I hope to read his other books.

Leave a comment