Irony and the impossibility of communication in traditional frameworks

Baseline irony pre-assumes a broadly shared set of agreed sociocultural norms and values. As the world has become increasingly interconnected, we can no longer rely on the assumption of a broadly shared set of agreed sociocultural norms and values due to the fact that the people we communicate with in any singular instance may not share the same sociocultural group that we originate from.

Previously, we could draw a simplistic dividing line along tribalistic identities: familiar is good; unfamiliar is bad.

This would have been maintainable and relatively stable by virtue of limited exposure to alternative sociocultural entities and/or disruptions to the tribal narrative by valid and reliable sources, such as representatives of external cultures or discussions and illustrations of outside cultural concepts by media or academia.

In an instance where alternative sociocultural entities trigger the emergence of a new narrative, these emergent narratives become increasingly difficult to discredit in relation to the amount of valid information, explanation, and exposure associated with any singular narrative.

Exposure across a multiplicity of forms simultaneously verifies or debunks the validity of the subject for consideration. This in turn establishes a form of cultural legitimacy and increases the dissolution of tribalistic virtue binaries based on familiarity.

Reality is revealed in the face of intensifying complexity.

With knowledge comes a recognition that there are a multiplicity of interpretations, often with substantive arguments, that cannot be sufficiently waved away by tribalistic narratives of familiarity. This is because local-centric narratives rely on the communal conception of the world as being very constrained and small. In being so constrained, the extent of accepted deviation from local norms is necessarily limited. Within the inner and outer perimeters of those established norms, even deviations are likely to be limited and familiar enough to pose no great disruption, even where disagreements occur. At the fringes, dramatic deviations from localised norms will correspond with a relatively inconsequential number of participants. If they begin to pose enough of a direct threat to the established norms, they are relatively easy to destroy or exile.

When confronted with complex reality and consequently a loss of tribal narrative coherence, there is also the potential for a loss of what was previously understood to be an immutable truth. Truth is heavily bound to our concepts of our own identity. When a previously immutable truth is displaced, its sudden loss of perception as an objective foundational reality can cause significant damage to the sense of identity and ego — both on an individual and tribal level.

The response is either:

- A: Accept the new understanding of reality, integrate it into the model thereof, and adjust accordingly;

- B: Reject the new reality and replace it with an artificial but familiar and simpler narrative that no longer displaces the sense of identity, thereby posing no threat to the ego.

If relativism is taken to better reflect reality, accepting the intensification of complexity, then this implies the loss of a centralised group narrative informing preconceived notions of truth, identity, norms, and values as being unquestionable constants.

Therefore an individual cannot rely on a presupposition that any given statement or narrative is automatically shared or even recognisable; especially given the de-localisation of interactions and audiences. Any given interaction is likely to contain differing viewpoints and backgrounds. This being the case, it renders the pre-establishment of any norm practically impossible.

Post-irony refers to a return to sincerity through an initial layer of irony. Meta-irony refers to the loss of interpretation or meaning, both on the part of the communicator and the recipient.

If the establishment of norms is no longer reliable, then the establishment of baseline irony becomes increasingly difficult. This drives the move towards post-ironic and meta-ironic means of communication.

If post-irony reaffirms a sincere assertion of a relative truth, while also acknowledging alternative positions, then we can still conceive of an authenticity or sincerity that acknowledges its own lack of omniscience — in the process reinforcing its own authenticity.

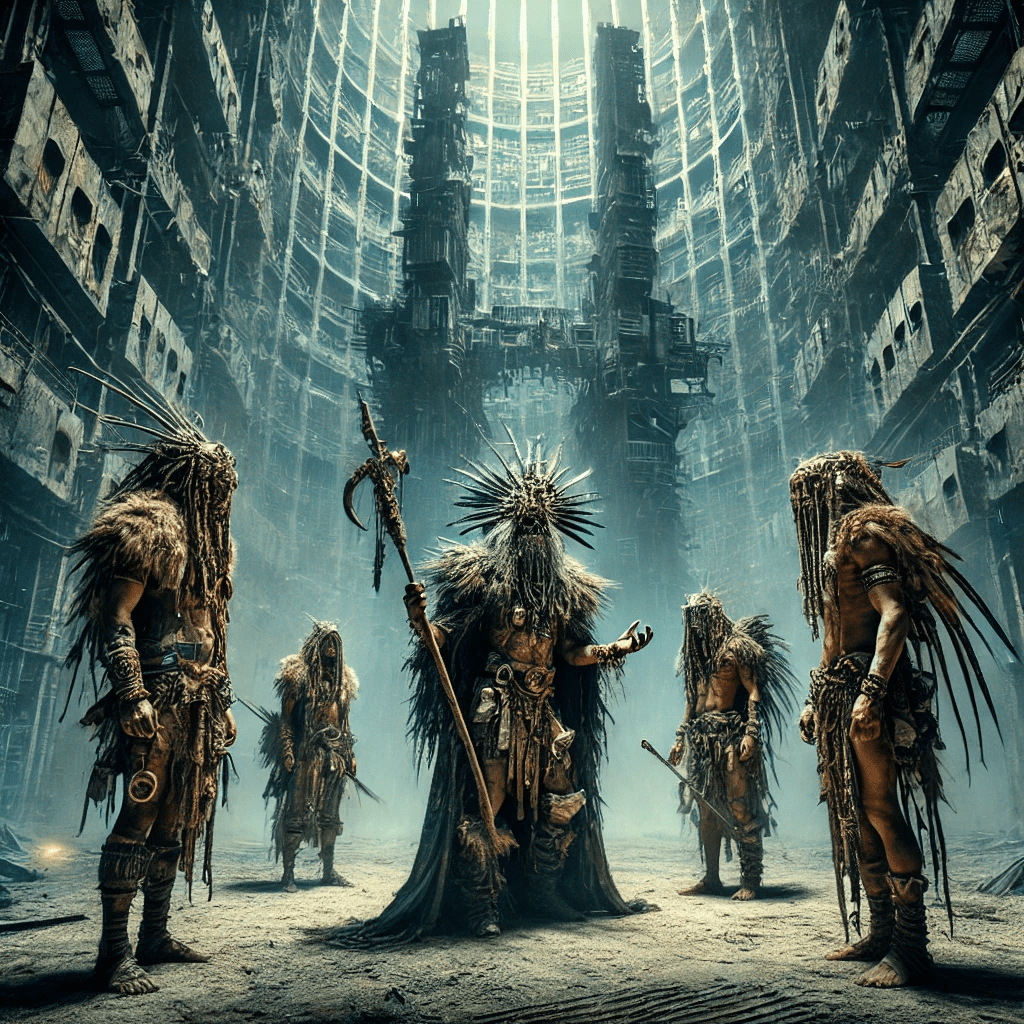

Meta-irony, then, seems to represent the acceptance of an impossibility of norms and shared interpretation of reality, to an almost Babel-esque extent, in that we do not trust the idea that communication is possible.

If communication is impossible, then significance and meaning is restricted solely to an individual. One interpretation of meta-irony, therefore, is that it seems to represent a kind of societal psychological solitary confinement or purgatory.

Leave a comment