“The whores all the smear on Revlon,

Yeah, they all look like Jayne Meadows,

But their mouths cut just like razor blades,

and their eyes are like stilettos”

Uncomfortably numb

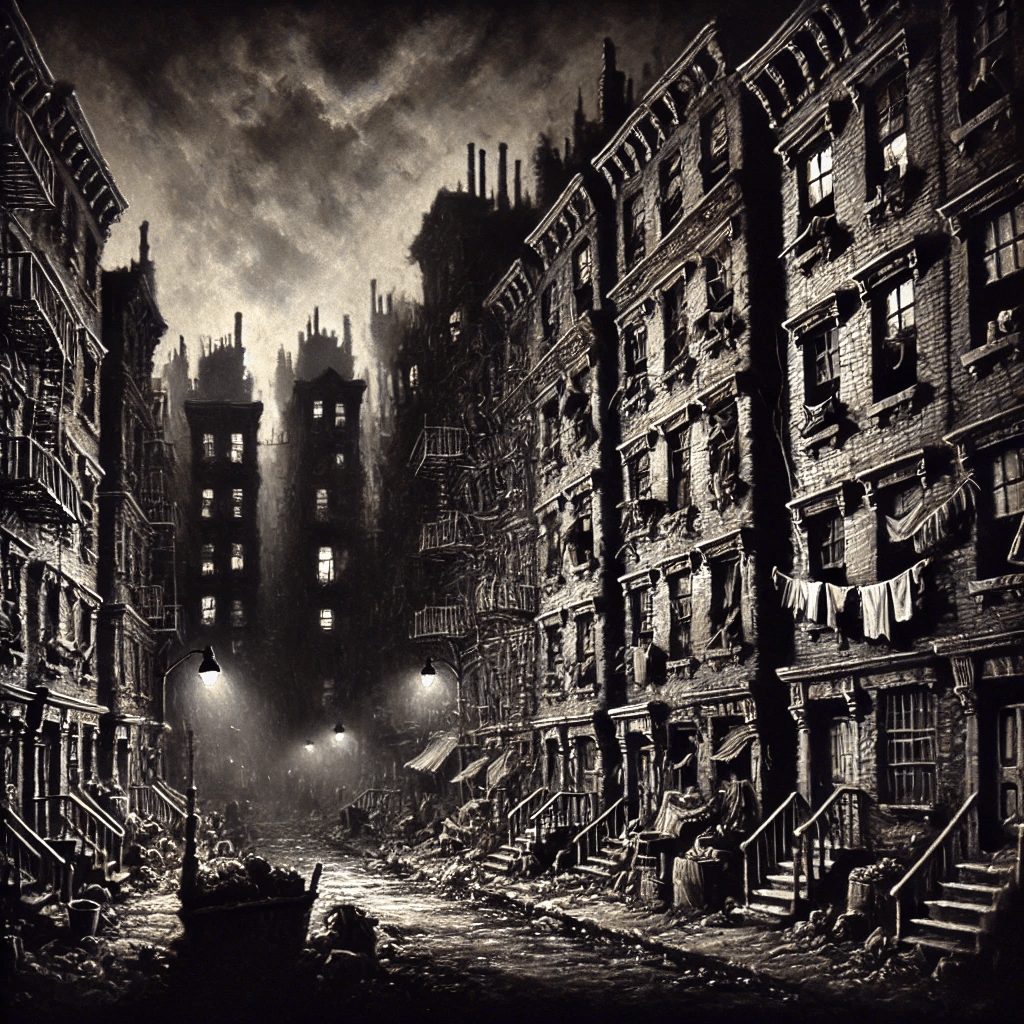

You have not read a book like Last Exit to Brooklyn. It is a thoroughly caustic book. At the same time, it is horribly numb. Not in the same way that Less Than Zero is numb. It’s a different texture of numbness. Less Than Zero‘s numbness is the hedonistic haze of drugs and alcohol and endless parties and clubs. It is, much like the characters, deliberately shallow. The characters have everything they could want, and between their youth and lack of challenge, their personalities are as surface level as their interactions. In contrast, Last Exit to Brooklyn is a deeply sad numbness. The characters here have absolutely nothing. It leads to cruelty, overcompensation, and tragedy.

Reading through this, I had the thought that the noir subgenre could probably resemble this if it wasn’t preoccupied with trying so hard to be gritty. The men are heartless and violent. The women are desperate and vicious. Bad people doing bad things to other bad people and taking advantage of the less bad. You don’t feel bad when their actions catch up to them, but you’re not triumphant either. There’s no justice porn here for the naively self-righteous.

Everyone is constantly searching for an exit. Like Less Than Zero, drugs and alcohol are their means of escape. Unlike Less Than Zero, Selby Jr’s novel has a visceral ragged edge to it. The point where Ellis’ novel stops, Selby Jr’s starts. This is not an environment that Clay and co. could snort lines in. It would eat them. Which is not the same thing as making a quality comparison, don’t get me wrong — I still think Less Than Zero is one of my favourite novels. What I mean is that their settings are polar opposites. There are no bored rich people with zero concept of reality here. When looking at Old Goriot, I noted that horror is banal and this is the same thing operating on the other end of the spectrum. We never saw the environments that Vautrin frequented, but you could take a stab at depicting them and they would probably look something like the stories in this book, set a couple hundred years back.

Extremity and enlargement don’t equate to quality – a typical failure of modern American media, but Selby Jr., like Ellis, like Ballard, like McCarthy, doesn’t try to run a sales pitch at you, trying to convince you how terrible the scenes are. He doesn’t make the mistake of taking four pages to laboriously bombard you with reams of adjectives. In fact, he does precisely the opposite.

My version has an introduction by Anthony Burgess of A Clockwork Orange fame. Usually, I skip introductions because the people who write them are extremely fond of the sound of their own voices and drone on for at least three times as long as they should, but when it’s the guy who wrote A Clockwork Orange is doing the talking, I’m listening. Credit where it’s due, Burgess doesn’t yammer on like that one self-indulgent prat that everyone knows, who thinks every time you go for drinks it’s an excuse to ‘hold court’. Burgess says his piece and he shuts up and for that he gets my respect.

Burgess describes the writing style as being close to reportage, “The direct, machine-like transcriptions of actuality which make up the book are one of the agents of shock.” There is no literary flourish here that allows members of the aristocracy to feel cultured and earns authors the Booker Prize. In fact, to illustrate the point brilliantly, some puffed up Conservative MP with a ‘Sir’ in his name prosecuted the book privately. He then escalated when the initial censorship didn’t go far enough for his liking. Long story short, Selby Jr.’s book was repressed from the end of 1966 until 1968, when the appeal process overturned the verdict.

This is exposed brickwork as text. You or I could not pull this off. If I handed that kind of writing to an editor, they’d wonder if I’d written it in ChatGPT. There’s an off-kilter staccato quality to it, at times it’s effectively a run-on list of events and thoughts that occur without any attempt at embellishment or explanation. There’s no differentiation between the internal and external worlds and at times the sentence lengths are as a means of characterisation or an indication of mental state. Somehow it works. Somehow it lands like a sudden fist in the face. And it will do that over and over again.

The book is set in the 1950s, and while we tend to view that era as a social archaism now, its characters are all recognisable. They aren’t people you’d want to know, they are the worst versions of people you’ve met, but you have met them.

Georgette’s chapter is a study in loneliness. A Benzedrine-addicted transsexual attempting to navigate a world that at best “tolerated more than accepted her, or used her as a means to get high when broke, or for amusement when bored.” She stumbles and fawns her way through periods of relative sobriety between parties and nights out and uses the states of inebriation or desperation as her sole means of shallow human connection.

It’s not clear if she’s actually trans or just into crossdressing, but reading between the lines, my interpretation would lean towards the idea that this chapter is dealing with trans identity long before it became mainstream discourse. Georgette refers to herself with feminine pronouns throughout, apart from once at the start of her chapter, though she only self-identifies as homosexual. I am not sure whether transsexuality would have been perceived more through the lens of transvestitism as the time, or how far transsexual identity would have been conceivable at the time. Naturally, public attitudes weren’t exactly tolerant in any case. It’s surprising how progressive and sympathetic this book is to a social group that is much-maligned a full 60 years later, let alone at the time of publication.

“Tralala didn’t fuckaround.” The irony. Tralala’s chapter doesn’t fuck around. This is someone attempting to become the ‘self-made woman’. She is the social media feminine empowerment story, the OnlyFans worker as liberation narrative, following a train crash vector you barely even want to rubberneck for it’s so miserable.

Tralala is a woman with a relatable desire: she wants money. Convenient for her, she has the equipment, and she knows how to use it. She is a prostitute. She doesn’t romanticise sex, it’s just a means to an end. That’s fair enough, through a certain lens even a mindset you can respect. Get in, get paid, get out. Who can’t relate? But fundamentally she’s bitter. Surrounded by thieves, thugs, and whores has turned her into little more than a fleshy reservoir for greed and spite.

I read her story as a commentary on the results of social immobility — yet another theme that is more and more prevalent in the modern world. She’s trying to escape her lot, but when she tries pulling anything better paid than sailors, she’s not so successful. Unwanted by the rest of society, she ends up going in small dead-end circles and this drives her mad. This feeling of being trapped at the bottom spirals hard and fast, and she ends up doing what everyone does: Block it out with drugs and alcohol. The climax of that particular chapter is as bitter as they come.

These characters embody what physicians in the UK allegedly identify as ‘Shit Life Syndrome’. Naturally, this isn’t exactly going to turn in the DSM5, but I think it’s extremely revealing when your country’s doctors notice enough a pattern between society and the maladies its members manifest, that they come up with a collective term for it that is not medical in nature and suggest they can do nothing for. You may also have heard it under the more media-friendly term ‘deaths of despair’, but ultimately the picture seems to be much the same.

Harry Black’s story takes up the majority of the book, feels drawn out, and becomes tedious. He is yet another abusive blithering alcoholic, only in this case he has stumbled over the fact that he’s gay. His arc circles through abusing and neglecting his family, getting drunk at his job and an ongoing strike, going to a bar, and occasionally something else happens.

Vinnie and co are there to beat the shit out of various people, do crimes, abuse various women, and speak in all caps.

Tommy is there to be a useless deadbeat dad.

What I’m getting at is that by the time you hit Harry Black’s chapter it’s hard to care. You get the impression that you can just leaf through sections of this without really missing anything once you’ve got the general gist of the story. It all runs into one greasy smear of human inadequacy. The character of this chapter is a prick, much like the character in the other chapter… And the one before that. At the end something bad happens to them. Shrug. One less idiot making the world worse. Was I supposed to empathize? How? Why?

None of these characters are relatable or empathetic, except for an old lass named Ada, who we meet at the end of the book. Her whole shtick is to be there to illustrate the petty-mindedness of all the other women around her, simply by being a normal person.

I didn’t live in the 1950s New York projects so I couldn’t comment on how much of a mess it was, but the writing has an effect that’s like being worked over with a carpenter’s rasp. You’ve got to wonder where the impetus to create that came from. If writing is speaking a personal truth, Mr Selby’s truth was very deep rooted and very mean. And it’s not easy to communicate that kind of hostility. A lot of people try, and usually they fail. They over-stylise it or they over-egg it or both. It just doesn’t hit the nerves because it’s trying so hard to be terrible. Forgive the repetition, but this is another example of how the effectiveness of horror comes not from the big stage-obscuring aggrandised moments. It’s in the relentless grinding accumulation of small pockets of tragedy and pain coagulating into a whole much more terrible than the sum of its parts that punches the hardest. Horror is often just banal. It’s rudimentary. It’s detached. It’s the normality that makes it. If you want to write a crapsack world without it just being edgy and juvenile, this book is another fantastic reference point.

From start to finish Last Exit to Brooklyn trudges along in a malaise of staggering hollow bitterness. The end is not really that different from the rest of the book, nothing has changed, and nobody has learned anything. People want to get drunk, or they want to get high, and they want to fuck, and they want to escape their lives for a half hour. Anything to make the world stop.

The themes of going through the motions and trying to block it out with alcohol and drugs and sex, ala The Sun Also Rises or The Rules of Attraction, etc. but this is more raw. It is a festering knife wound rubbed with salt and vinegar and chased with ketamine. It just gets a bit tiring. For the record, the book would have been worse if the people in it weren’t so disposable. You understand how their claustrophobic environment shapes and warps these poor bastards, but even in their wretched state they are so deplorable that any sense of empathy is completely absent for 95% of the cast.

Like Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition, Selby Jr. achieves what William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch couldn’t. Naked lunch was effectively shock jock literature. It was spectacularly written, but it was trying so hard to shock you all the time and had a grand total of about three themes it would cycle through. You got the impression of Burroughs squatting in the corner the leering at you, just waiting for you to get all outraged and self-righteously throw the book away. In reality, you just end up sighing and shrugging at the edgelord juvenility. This doesn’t happen with Last Exit to Brooklyn. There’s no sense that Selby has set out to deliberately get a rise out of you for his own amusement. It will get a rise out of you, but it’s less an idiot trying to press your buttons, and more a serious man pasting you hard in the face. Harder than you expected him to.

I realised after the fact that this book effectively falls into the naturalist style of fiction, which I hadn’t deliberately chosen to do after Old Goriot but does offer an interesting connection and point of comparison.

It’s easy to come at this one with a nonchalant shrug because you’ve read a bunch of other heavy stuff. You’d be underestimating it. And you’re in for a shock. I’m going to assume a lot of people had the same experience.

I need to go read something happier.

Leave a comment