What can’t you put in a fictional advert?

On Warren Street a tall metal posterboard shows me a wine glass the Spanish Inquisition could have taken inspiration from. Glass needles stab in every direction. You’d need mail gauntlets to drink from it. You probably shouldn’t. “If only it was this easy to see a spiked drink,” the billboard tells me. Notion assures me that it’s one workspace for every team, from the top deck of a passing bus. The giant screen glaring from the side of the slatted Spaces In-Between cube informs me that the Saudi Red Sea is “where two worlds make one.” In Tottenham Court Road station, The Phantom of the Opera is there… inside… a backlit frame mounted on a pale wall.

There’s a questionable figure that the average person consumes 10,000 ads per day. This is unlikely, according to The Drum – it works out as one advert for every 6 seconds that any given individuals eyes are open across a 16-hour period of being awake per day. The 3-5,000 figure seems to be just as questionable, stemming from a 1968 book by a couple of Harvard business professors. The Drum’s own ad-hoc count by an editor came to a grand total of 93 ads they were consciously aware of over the course of a 16-hour period. They conclude, “This doesn’t mean, of course, that others aren’t exposed to far more ads: other demographic groups, for example, watch far more commercial linear TV; others will have more ad-heavy commutes. But 9,907 more exposures every day? Now that’s hard to picture.”

Still, even in the age of ad blockers and remote work, we are surrounded by advertising. Like it or not, you’d need to pretty much become a literal cave man in the Appalachian Mountains before you could escape the long fingers of the marketing department. But one area in which advertising is remarkably sparse, is fiction. Whether written, filmed, interactive or other, advertising is an oft-overlooked element of a setting. This is especially interesting for the literary and adjacent camps, because copywriting is one of the major components of the marketing and advertising industry.

Marketing in fiction

When we think of marketing and advertising we tend to think of them in their contemporary forms – a torrent of banners, pop-ups, social media spam, billboards, flyers, posters, car covers, door covers – if it has a surface, someone has paid an agency to plaster a piece of marketing onto it.

Given that we’re talking about marketing in the context of fiction, you might instantly think that restricts thinking about advertising in your setting to relatively modern eras, or the realm of the science fiction. Not so fast. What’s a witty invitation on a chalkboard outside an old pub or café? What would you call a market stall cry? If you played the first Divinity Original Sin, your strongest memory is probably the Cyseal Market. There’s a dozen vendors there, all shouting out their pitches, and it’s notable that the writers went the extra step. The vendors are not just yelling ‘get yer vegetables, ‘alf a pound a copper’, or what is called a ‘direct’ approach, wherein you sell the product without gimmicks, you just state the product and the value proposition. If you’ve ever seen a Facebook ad that is just ‘service’ ‘price’ ‘click now’ format – that’s direct marketing. Instead, the writers at Larian gave the vendors a whole bunch of kooky and memorable market calls. Why is that important? Because now I remember “Not in the mood for cheese!? That excuse has more holes than a slice of this fine Gorgombert!” with more clarity than the birthdays of my family members… The fake adverts worked.

It’s all sales, and copywriting is a very old form of sales, we just have a fancy name and an industry for it now. We don’t necessarily have to be some dork in an ill-fitting suit lugging a briefcase around and harassing housewives with ‘the latest in domestic technology’. The first line of Robert W. Bly’s The Copywriter’s Handbook is a quote by the president of a retail advertisement agency, Judith Charles, “A copywriter is a salesperson behind a typewriter.”

Most stories, no matter the medium, involve commerce at some point or another. Harry Potter buys a broomstick, John Wick buys a boomstick, Hemmingway’s nameless merchant bought some new kicks… but there’s often a surprising lack of marketing. Sure, Sweeny Todd could probably get by on word of mouth, the Victorian equivalent of ‘organic’ traffic, if you like. But Benjamin Barker? Benjamin Barker would need a hook – ‘Come for the pie, stay for the shave’ or something. Hell, even the satirical corporate dystopia of Jennifer Government, in which the protagonist is a former advertising big wig, and the antagonist is a marketing executive, is surprisingly sparse on advertorial copy. Which, given the character, she would probably notice everywhere and analyse out of pure reflex. On reflection, the number of straplines, follow-up emails, and product descriptions is striking in its contextual scarcity. Instead, we’re just asked to take it on faith that Ms. Government is her setting’s equivalent of David Ogilvy. Your mileage may vary, but that may have been an oversight on Max Barry’s part. And he’s far from alone.

What is copywriting?

First thing’s first: This has nothing to do with the legal term, ‘copyright’ which is a source of endless confusion for people. Freelance copywriters, when asked what they do, have to clarify the term ‘copywriter’ 99% of the time. In general, copywriting refers to any text created for the purposes of marketing and advertising. Which is awkward, because ‘copy’ is just media industry jargon for ‘text’. If you are publishing a book or an article in a journal or other outlet, the editors might refer to ‘manuscript copy’.

If ‘copy’ is a ridiculous industry synonym for ‘text’ then why am I talking specifically about marketing and advertising? I guess the most practical answer to that seem to be that the job terminology is entirely dependent on what you are writing. If you write books, you’re a ‘writer’ or if fiction-specific you might be referred to as a ‘novelist’. If you’re writing news and editorials, you’re a journalist. And if you write tag lines, strap lines, web pages, product descriptions, and a range of other sales-based text, then you’re a ‘copywriter’. So, despite the fact that all of these different writers are producing ‘copy’, only one kind is identified as a ‘copywriter’. Weird, but I don’t make the rules.

How does copywriting apply to fictional settings?

“Sure,” you might say, “whatever. Sounds great, but I’m trying to build a setting, not sell people random tat.” And you might have a point. On the other hand, sales is the oldest profession. I know what you’re going to say, but even sex workers need to advertise. Many of you might not be old enough to have gotten up close and personal to a public phone box, but ask anyone over the age of about 25 and they’ll give you a misty-eyed reminiscence of the esoteric collection of seedy leaflets, racy stickers, and questionable posters that would plaster the insides of these contraptions, with phone numbers in bold for any number of ‘services’ and ‘specialists’.

Sales is a wide term, however. We are only concerned with the advertising. We are not, for example, the guys who spend Q4 ringing vast lists of clients to confirm subscription renewals with spreadsheets full of carefully calculated percentages and offer margins. The copywriter needs to make the product sound good enough to ensure a conversion. Ever looked at product on an ecommerce site, read the product description, and clicked ‘add to basket’? Copywriter. Ever left something in a basket on an ecommerce site and got an email the next day heralding the product as if it were the second coming of Christ? Copywriter. Do you have an advert from a decade ago that you can somehow remember with better clarity than the name of your second spouse? Copywriter.

“Yeah. Ok. That sounds great. I’m not doing that,” you protest. But you are, I insist. In a hundred different ways, you are trying to sell your audience your setting. You are trying to convince complete strangers that your fictional place is worth buying into. Sure, you aren’t selling a direct product, but you might think of it as selling an investment. An emotional investment is as much a resource as any other, and alongside it comes another investment that might actually be worth more than its weight in gold: time.

Your audience has a finite amount and there are a trillion other products, and pieces of media, competing for it. If you can get your audience to invest in your product, your setting, either intellectually or emotionally, you’ve got a down payment on their time. If members of your audience have questions and curiosity, they might spend time think about the thing you’ve created. The more time spent thinking about it, the deeper the investment. If they become invested in a storyline or a theme, they will spend time thinking about those themes and those characters, and the implications and the connections related to them. What else does a fan wiki represent? Intellectual and emotional investment. And there are hundreds of them. People can devote dozens of hours of labour to elaborating on any number of aspects when sufficiently invested.

The more naïve of you immediately condescend: “Oh, come on – that’s a bit much, isn’t it?” To you, I present, the Marathon Wiki.

Not convinced by just one example? That’s reasonable. What about the SoulsBorneRing theory crafting community? Can you tell me that guys like VaatiVidya or SmoughTown haven’t invested a great deal of emotional and temporal resources into the settings created by FromSoftware? To the point where they’ve managed to earn money from their obsessive mining of FromSoftware’s creations. Ok, fine, FromSoft has a couple of mental fans. Who cares? You should. Because it ain’t just FromSoft.

- Tolkien has Arachîr Galudirithon, Men of the West, Nerd of the Rings, and of course a gigantic wiki featuring almost 7,000 articles, amongst an endless number of other Tolkien archivists and scholars;

- Martin has A Wiki of Ice and Fire, David Lightbringer and Alt Shift X;

- Herbert has the Dune wiki and Quinn’s Ideas;

- Cyberpunk has the Cyberpunk Wiki and WiseFish;

- Asimov has the Foundation wiki;

- Abercrombie has the Circle of the World Podcast.

And on and on; if there’s a big fictional project somewhere, there are fans who will spend an absurd number of hours on it.

How does in-world marketing benefit the setting?

Ok, but none of that has anything to do with advertising.

Correct you are, astute reader. My point is that in-setting advertising is a fantastic way to sell your setting to your audience. Consider games like Grand Theft Auto or Cyberpunk 2077 – in those settings a surprising amount of effort has gone to the in-world marketing material. One of the most memorable parts of Less Than Zero is the billboard strapline, ‘disappear here’.

Here’s the great thing about fictional marketing: You don’t actually have to sell any products. You don’t have to adhere to the constraints and concerns of actual real-world advertising. Nobody is throwing millions of pounds at Facebook ads expecting a wildly unrealistic return on investment. You will never need to worry about conversion rates. You will never have to deal with a client screaming at you in January because their sales figures didn’t come through in December, and despite the fact that a lack of sales could derive from any combination of a hundred factors, they’re committed to blaming you. You are free to do whatever you want.

Nevertheless, if you want fake adverts that read like real adverts, then it can help to know a little more about how the sausage is made. Contrary to what you might expect, it isn’t just throwing tits against a red background above the name of a product. If only. There is a process and a structure to all of the forms of advertising that you see in the world – of course there is, it’s an industry and industry seeks efficiency. No matter how artistically informed. So it is with copywriting. There is a method to the madness that goes a little deeper than just gaslighting you into feeling insecure – and we’ll get to that later on in this series of posts. Also, as a rule – no puns.

Grand Theft Auto‘s commitment to mocking the contemporary world, employs in-setting marketing to great effect. They can do that because most of their material would never get past advertising standards regulators, let alone be approved by a client. But we all know that’s not the point. They are there to add detail and depth to the pastiche of modern society. They take an element or trend in consumer culture and put it under a magnifying glass, emphasising the absurdity through the use of humour and exaggeration. Grand Theft Auto isn’t going to be winning anything at the MarCom Awards, but the in-world adverts are always going to be mocking the nature of advertising itself, which works because the global automotive ad spend was $42.4 billion in 2022 – the connection between cars, American culture, and marketing, is basically a triangle. Without having to worry about constraints on subject matter, Grand Theft Auto can get away with a lot more than the advertising industry can in the real world. Because of that, you’ll see a lot more overt sexualisation and provocative jokes than you would in the real world.

Then again, tell that to the Fiat Punto Mk2 car advert – Broadcast 11th January 2000 (UK) ad? Usually, I hate people who claim you’d never get away with such and such anymore, they’re usually trying to push some “subtle” narrative ‘abaht dem wokies, like what I saw inna Tel-a-grahf da uvva day’; but I’d put money down that there’s absolutely no chance you’d get away with that ad now. But you don’t have that problem in fiction. Is your setting a hyper-consumerist libertarian’s idea of utopia? Here’s advertising with no brakes. Nipples on a billboard? No problem – hell, go the full Hicks with it.

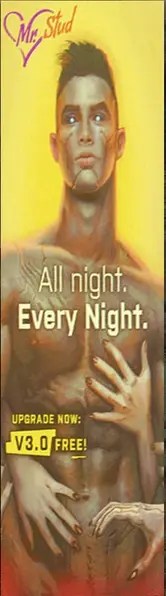

This is what Cyberpunk 2077 does upfront. You won’t make it far from V’s apartment before you come across a ‘Mr. Studd’ ad, which will urge, “don’t be soft, upgrade now.” The actual ad copy in Cyberpunk’s setting is mixed at best, but that’s not the point. It’s about communicating the state of the world in which the characters live. The visual imagery is focussed on extreme evocation. There is no coyness here, anything is allowed if it gets your attention. From which you learn about the ethos of that world – in Night City’s case, that the streak of puritanism that runs through real-life contemporary American culture, is long gone in this setting. If anything, ‘sin’ is just another marketing tool by which to evoke a response. And instantly, the audience understands a bit more about where they are.

(Curiously, this ad features a mispelling of ‘Studd’, with only one d…)

How does this help the audience and what are you priming them for?

Less Than Zero‘s ‘disappear here’ is priming the audience for the themes of slipping through the cracks of society. The fact that the message is up on a billboard – a physically imposing invasion of attention that represents money and influence on the part of industry – reflects the consumerism that the society depicted is submerged in. The mythos of contemporary western society is that if you have enough money then you can stave off being forgotten. This in turn feeds into the narrative arc by which we are exposed to a crescent of flailing abandoned rich kids as they defy that very notion. Despite the fact that they live at the societal apex, we watch them fall through the cracks of a world that doesn’t know they exist to begin with and doesn’t notice or care when they are gone. The traditional image of the fallen person is accompanied by grime-smeared bathrooms and the trash-strewn alleyways, buy in Ellis’ novel this is replaced by immaculate ornamentation and glamorous bachelor pads. The social elite occupy the same role as the social underbelly, shooting heroin and turning tricks in disparate hotel rooms to pay off insurmountable debts. They just drive nicer cars.

‘Disappear here’ emphasis a world in which all individuals become interchangeable and disposable, a theme Ellis revisits across his books. That is a truth of the real modern world – even more so as we are no longer conceived of as individual humans to the real digitised world. We are, instead, rendered down into vectors for shareholder value maximisation by automated systems that profile us with data aggregated from a hundred sources. We are economic units on the conveyor belt that will feed us and our children, and our children’s children, into the insatiable furnace of the economy. ‘Disappear here’ as an in-world advert reflected the real world of the mid-1980s. Whether intentional or otherwise, that reflection has only grown sharper.

Ads, products, theme and tone (theme and tone!)

You don’t have to turn yourself into David Ogilvy. You’re not trying to sell a product, so much as you’re using a fictional product or company to emphasise an aspect of your setting. In doing so, you are highlighting those individual details, which in turn can add one more aspect to the collage of elements that make up a convincing fictional setting. Nevertheless, there’s more to adverts and copywriting than might be expected by the average bear. It can help to have a foundational knowledge of the process so you can be as close to, or as deviated from, actual marketing as fits your setting.

Therefore, thinking about the adverts in your setting can serve as a vector to reinforce or accentuate a theme or an idea in a story. You can repurpose advertising to illustrate and add flesh to the kind of tone you want to convey to your audience. Whether that is a central theme, or a secondary influence, or even if you just want to play with an idea but can’t justify devoting narrative real estate to it. You can throw anything up on a fictional billboard and let people respond to it – both the fictional and the non-fictional.

Leave a comment